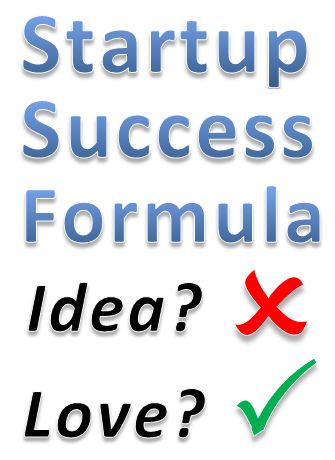

What will hold startup founders together through those ‘sense of impending doom’ moments? The fact that the business idea is great? Y Combinator’s Paul Graham thinks not: the relationship between founders has to be more important than the venture.

Paul’s rationale is based upon what I call the ‘Captain and Tenille’ theory.

The theory basically says that all startups go through moments when things look utterly hopeless.

If an investor is about to commit to founders whose only reason for working together is the business idea, then they need to anticipate the fact that at the almost inevitable point where, in the course of developing the solution, the underlying idea convinces one or more founders that it will undoubtedly fail, the founders will split and the investor will be potentially left with nothing.

Paul expounds his theory here.

Personally, I think this will confuse many investors.

The conventional investor will probably feel that if the idea starts to look so unworkable that it convinces the founders that it’s a definite no-hoper, then it doesn’t matter if the founders stay together or not, because the only thing the investor was investing in was the success of the venture, which was predicated upon the fact that the idea that it was based upon would not be a failure.

To a conventional investor, a team that stays together after giving up trying to implement a failed idea may still constitute a commendably loyal friendship, but it also amounts to a disastrous waste of investment capital.

Although Paul deals with this concern by saying that “mistakenly continuing to work out of misplaced loyalty to your pal is a good thing, because eventually things get better” the conventional investor’s mind may still not be put at rest: if it’s a big enough impasse for even the possibility of giving up to be on the table, the investor themselves (especially if this was an ‘all eggs in one basket’ angel investment) may not survive the resulting potential heart attack.

I say ‘conventional investor’ in this context with a precise meaning.

Y Combinator has a rather unique trick up their sleeve, as far as their attitude regarding ‘it’s not really the idea that we’re investing in’.

They really, really, really mean that the idea doesn’t matter.

This all became clear to a lot more people than myself on March the 13th 2012.

They made this announcement:

Apply to Y Combinator without an Idea

From the Y Combinator website

“Apply to Y Combinator without an Idea

We’re going to have a separate application track for groups that don’t have an idea yet.

So if the only thing holding you back from starting a startup is not having an idea for one, now nothing is holding you back.

If you apply for this batch and you seem like you’d make good founders, we’ll accept you with no idea and then help you come up with one.

Why are we doing this?

Partly because we realized we already were.

A lot of the startups we accept change their ideas completely, and some of those do really well.”

This approach is not because they believe that ideas don’t matter at all, or even because they don’t matter as much as the relationship between the founders.

Here’s what makes Y Combinator’s applicant assessment criteria unique:

Ideas at the outset are treated by him as reflecting the capability of the founders to do ideation effectively, which is an absolutely indispensable sign to Paul that the founder has the right kind of mind to found a potentially successful innovative startup venture.

Y Combinator’s enviable track record proves that Paul undoubtedly has the skill to accurately determine whether the applicant can do this, even if they haven’t ‘brought an idea (or an idea that he wants to back) to the table’.

He’s also looking for convincing evidence of unswerving tenacity and commitment in all the prospective founders (Y Combinator’s Jessica ‘Social Radar’ Livingston, Paul’s wife, has historically done the validating of this, because, as Paul himself admits, he can be blindsided on it).

The way the ‘founder relationship criteria’ play into the rest of this formula is not just what Paul says in the video clip about ‘continuing out of misplaced loyalty… is a good thing… because things eventually get better’, but because, if the idea does indeed prove to need to be abandoned, then a restart, essentially continuing to fund and support the startup, but completely dropping the original idea and starting a new project with a completely different idea, is something Paul has no objection to whatsoever under these kinds of circumstances.

How often do you hear a startup investor proclaim their amenability to restarts?

So when I say ‘conventional investor’, I certainly don’t include the kind of investor who:

- is expecting/prepared to invest in projects that they may be ‘co-ideating’ with the founder

- sees re-starts as perfectly acceptable

- is looking for love in all the right places (for investment)